Toilet Map is a Google Map of public toilets in London. The map is available from your desktop, as an iPhone and Android app and from a dedicated mobile site. Toilet Map currently shows the location of nearly a 1,000 public toilets in London.

It is possible to refine the toilets shown by male, female, disabled and whether the toilet is free or has a charge. If you click on a marker you can view details and see the toilet's opening hours.

If you know of a toilet not on the map you can add it by completing a short form.

Find Toilet

If you are ever desperate for the loo in Denmark you will be thankful for this Google Map. Find Toilet is a map of public toilets with some excellent search options.

Using the map it is possible to find a toilet by town or by region. It is also possible to search for public toilets in a radius of any given location. Lastly, you can also search for a toilet by type, for example handicapped or unisex toilets.

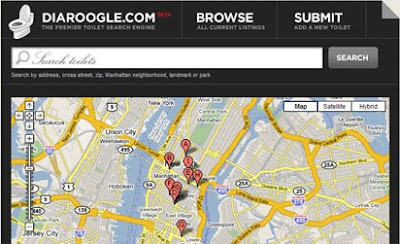

Diaroogle

Diaroogle is a community submitted map of Manhattan toilets. The site says that is is for "the discerning, on-the-go defecator who is brave enough to use a public bathroom, but still demands a hygienic and private bathroom experience."

Each mapped toilet tends to come with a general report on its cleanliness and occupancy levels. You can search the map by address, cross street, zip, Manhattan neighbourhood, landmark or park and probably most usefully can access the map from a mobile phone.

LooToGo

LooToGo is a Google Map that shows the locations of public toilets in Germany. The site currently has over 28,000 restrooms in its database.

It is possible to search the map by location. If you click on a map marker you will be taken to the reviews section for that public toilet. If you know of a loo that is missing you can even add it to the map.

LooToGo also comes with an iPhone app, so now you can find your nearest toilet when you are out and about and caught on the hop.

Also See

- SitOrSquat.com - thousands of toilets mapped around the world

- NYRestroom.com - A map of New York restrooms